Celiac Disease Panel: IgA and IgG anti-Tissue Transglutaminase/ IgA and IgG anti-Deamidated Gliadin

The Changing Incidence of Celiac Disease

During my medical school rotation through pediatric medicine at the University of Illinois in 1969, I was taught that Celiac Disease (CD) (Gluten Sensitive Enteropathy) was considered to be an uncommon disorder. But, that was before the day of endoscopes equipped with cameras that can seek out key areas to biopsy. It was long before serologic testing was available that could justify the painful, gagging, clumsy endoscopic methods available back then. Consequently, only the most severely affected cases of CD were detected. As reported in the September 16, 2009 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, CD is now considered to occur in about 1% of the “Western population.” This extraordinary difference in estimated incidence of the disease has come about largely due to improvements in laboratory testing methods that provide a noninvasive comprehensive screen that can detect even the most mild cases of CD and recognition that our earlier clinical and diagnostic methods only allowed us to find the tip of the proverbial iceberg of this extraordinarily heterogeneous clinical disease.

Symptoms That Could Indicate CD

Unfortunately, the symptoms of CD are among the broadest of any disease category. They range from severe cases presenting with abdominal bloating, diarrhea, weight loss and obvious nutritional deficiencies to cases that are totally asymptomatic. This difference in symptoms relates to the extent of damage to intestinal villi, the individual’s usual diet, and the duration of the disease.

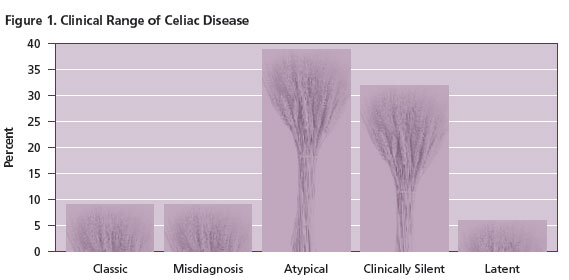

The “classic” severe presentation mentioned earlier only occurs in about 10% of patients with CD (Figure 1). Another 10% of cases are misdiagnosed and carry other diagnoses of other gastrointestinal conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, chronic fatigue syndrome or even chronic intestinal infection. About 40% of patients with CD cases have atypical presentations in that they lack symptoms related to the gastrointestinal tract, but do suffer from chronic problems related to malabsorption such as iron deficiency, short stature and osteoporosis. A third of the cases are clinically silent, yet they do have bowel damage. Lastly, a few individuals have latent CD with no evidence of current disease or demonstrable bowel damage, but they have either had CD at an earlier age which is no longer clinically evident, or they will develop active CD at a later time.

The most common symptoms in adults are listed in Table 1. Some symptoms seem paradoxical, such as the presence of diarrhea in the more classic presentations, but also constipation in a few individuals. Other symptoms, such as mood swings may relate more to electrolyte imbalances. In children, the disease is often discovered when the child tracks low on height and weight charts, occasionally accompanied by symptoms suggesting a gastrointestinal basis (Table 2). About 15% of patients with CD have Dermatitis Herpetiformis (DH), a skin disease characterized by scaly, itching skin especially over elbows and knees. Most patients with DH have focal flattened villi, but usually do not develop diarrhea.

Table 1. General symptoms in adults

| Abdominal pain (cramps, bloating) |

| Abdominal distention |

| Flatulence |

| Weight loss |

| Diarrhea |

| Constipation |

| Increased appetite |

| Foul smelling light colored and/or loose stool |

| Susceptibility to bone fractures |

| Skin symptoms (Dermatitis Herpetiformis) |

| Edema |

| Bleeding Diathesis |

| Emotional swings |

Table 2. Most common symptoms in children

| Failure to thrive |

| Inadequate Growth |

| Weight loss |

| Diarrhea |

| Vomiting |

| Abdominal distention |

| Emotional swings |

CD patients are more likely than the general population to have selective IgA deficiency (usually clinically silent, though they are prone to develop allergies and may have anaphylactic reactions to intravenous infusion of components containing IgA), other autoimmune disorders such as thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes mellitus, and genetic conditions such as Down syndrome and Turner syndrome. A useful summary of the groups at increased risk for CD was compiled by Goeken and Kingery (Table 3).

Table 3. Groups at increased risk for CD

| Group | Percent Positive* |

| Dermatitis Herpetiformis | 100 |

| First-degree relative of CD patient | 5-15 |

| Down or Turner syndrome | 9 |

| Idiopathic infertility | 6 |

| Growth failure (children) | >5 |

| Autoimmune disorders (Diabetes mellitus type 1, Sjogren’s) | 2-6 |

| Iron deficiency anemia (also B12 and folate deficiency) | 4-5 |

| Osteoporosis | 2-3 |

| Chronic Fatigue | 3 |

*Percent found to have CD, Data modified from Goeken and Kingery

Etiology and Pathology of CD

CD is an autoimmune disorder with a genetic predisposition and an environmental trigger. Individuals with CD almost always have HLA-DQ2 and/or HLA-DQ8 genes. Unfortunately, about 30-40% of unaffected individuals also carry one of those HLA genes. Because of this large number of unaffected who carry those genes and the fact that small numbers of individuals lacking those genes do develop CD, HLA screening is not effective to rule in the disease.

The environmental trigger for CD is gliadin, an alcohol-soluble antigen from wheat, rye or barley gluten. The pertinent part of this molecule is a 33 amino acid sequence that is difficult to digest and is deamidated by tissue transglutaminase (tTG). The deamidated fragments bind to antigen presenting cells that are either HLA-DQ2 or -DQ8 positive thereby inducing a helper T cell proliferation. As a result, the intraepithelial lymphocytes injure adjacent surface epithelial cells eventuating in villous damage. The damaged surface epithelium not only compromises the ability of the bowel to absorb nutrients, but also permits access of the intestinal contents, including microorganisms, to the lamina propria.

Both cellular and humoral immunity develop to gluten moieties and tTG in patients with CD. After a genetically susceptible individual develops an immune response to gluten, further ingestion of wheat, barley or rye exacerbates the immune response and damages the villous epithelium (shorted or flat villi, damaged surface epithelial cells, increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, and increased mitoses in the crypts). Abstention from gluten in the diet results in recovery of normal villous architecture and reversal of the symptoms. Fortunately, a wide variety of gluten-free food is available that individuals with CD can choose, but they still need to carefully examine the product label to be sure that a component of gluten is not used in the manufacturing.

As noted, the vast majority of people with HLA-DQ2 or –DQ8 do not develop CD despite the ubiquitous exposure to gluten in the Western diet, indicating that as yet unknown factors are operating in the initiation of the disease. Further, while most cases of CD begin in childhood, individuals may develop symptomatic CD at any age. Clearly, we still have much to learn about the initiation of CD in genetically susceptible individuals.

Although not a particularly helpful screen, genetic testing may be useful for testing family members of an affected patient. It is also useful in individuals who had been placed on gluten free diet, but due to the manner of the original diagnosis, may be still uncertain if they truly suffer from CD. Here the lack of the appropriate genes is strong indication that the individual may have another gastrointestinal process that requires further evaluation by endoscopy, or other techniques.

Histopathologic Testing For CD

Prior to the availability of robust serologic testing, the only recourse was to perform endoscopy on a patient with sufficient symptoms and examine the biopsy. If the histologic features were compatible with CD, the patient was placed on a strict gluten-free diet. After the patient recovered normal bowel function, a second endoscopy was performed to demonstrate the return toward normal small intestinal architecture. To be certain that one was not dealing with a transient bowel process, however, the patient was challenged with a gluten-containing diet followed by yet a third endoscopy that needed to demonstrate return of the histopathologic feature of CD. Happily, serologic testing has not only broadened the scope of patients who can be tested, but has minimized the amount of invasive testing required to substantiate the presence of the disease as well as adherence to an appropriate gluten-free diet.

Endoscopic biopsy evidence is still considered the “gold standard” for CD. Yet, since the disease can be patchy and the interpretation has a subjective component, serology has become an important, noninvasive way to diagnose CD. The presence of strongly positive serology with confirmatory genetic testing for HLA-DQ2 and –DQ8 in the presence of appropriate symptoms can indicate CD even in the presence of negative biopsy information. Nonetheless, in cases with negative serologic studies (especially in IgA deficient patients) who continue to have symptoms suspicious for CD, small intestinal biopsy should be performed to detect either CD or one of the gastrointestinal conditions noted above that can provoke symptoms that mimic CD.

Serologic Testing for CD

Slightly over a decade ago, two types of serologic tests emerged from the earlier attempts at developing immunologic assays to detect CD. Indirect immunofluorescence (IFA) tests (the most useful being IgA anti-endomysium (EmA) ) and enzyme immunoassay (EIA) tests (the most useful prior to tTG was IgA and IgG anti-gliadin (anti-Gli)).

The original anti-Gli assay was relatively nonspecific because it used intact gliadin. The IFA IgA anti-EmA tests were highly specific for CD, but were costly and subjective. Although the IgA and IgG anti-Gli were neither as specific nor as sensitive as the IgA anti-EmA test, they were objective, could be used to follow response to therapy and the IgG anti-Gli was helpful in a few cases of CD with IgA deficiency.

In the past few years, dramatic improvements have been made to CD serology. The antigen responsible for the positive anti-EmA antibody has been identified as tTG. With purification of this antigen, reliable and objective EIA kits for both IgA and IgG anti-tTG are now available that we recommend replace the subjective IgA anti-EmA test. However, a few cases of CD are negative for IgA and IgG anti-tTG as well as to IgA anti-EmA.

As noted above, it is deamidated gliadin (dGli), not native Gli that binds to the HLA- DQ2 or –DQ8 cells. And manufacturers have found that the use of dGli in their EIA assays have greatly improved the sensitivity and specificity of that test.

A caution on serology is that the anti-tTG and –dGli are affected by antigen stimulation, i.e., in this case diet. The tests have maximal sensitivity when the individual is ingesting a normal (gluten containing) diet prior to testing. If individuals had been placed on gluten-free diets prior to testing, a false negative result can occur. However, because of this same feature, serologic studies may be helpful when individuals are being monitored for compliance with a stringent gluten-free diet. Elevation of specific antibody levels suggests noncompliance, or inadvertent ingestion of gluten (perhaps due to its use in the processing of otherwise non-gluten-containing food).

Lastly, not only are the new breed of EIA tests more specific and sensitive to detect the IgA-competent CD patients, but they also have produced a higher degree of reliability in detecting IgA deficient patients who have CD. Villalta et al reported that IgA deficient patients produce IgG antibodies against both tTG and dGli that can be detected with the newer available EIA products (Table 4). Moreover, IgG anti-dGli proved to be effective in detecting CD in IgA competent and IgA deficient patients. Both the IgG anti-tTG assay and the IgG anti-dGli assay were more effective at detecting CD than the IgG anti-EmA test Table 4. This, along with the subjectivity of the EmA testing is why we recommend using a screening panel consisting of IgA and IgG anti-tTG and –dGli when testing individuals for CD. Further, because IgA deficiency has an increased occurrence in patients with CD, the use of both IgG and IgA specific assays as the screening test allows detection of the vast majority of patients with CD, even in the presence of IgA deficiency.

Table 4. Serologic Results in 28 IgA deficient cases (21 children, 9 adults) with CD on normal diets

| Test | Sensitivity with Age-specific cut-offs | Sensitivity with Manufacturer’s cut-offs |

| IgG Anti-tTG | 92.9% | 85.7% |

| IgG Anti-EmA | 77.8% | 77.8% |

| IgG Anti-dGli | 92.9% | 92.9% |

Data from Villalta et al.by both age-specific (to correct for lower IgA levels in young children) and straight manufacturer’s cut-offs.

Summary

CD is one of the most common diseases in Western medicine. However, due to the wide variance in presentation, many clinically affected cases are not tested for this treatable condition. Reliable serologic testing permits cost-effective, noninvasive screening of large numbers of individuals who previously may not have been candidates for endoscopy. Because of dramatic improvements in EIA testing for CD, Warde Medical Laboratory recommends that individuals suspected of having CD be tested with a panel of: IgG and IgA anti-tTG and IgG and IgA anti-dGli.

Further Reading

- Dieterich W. et al. Identification of tissue transglutaminase as the autoantigen of celiac disease. Nature Medicine. 3:797-801, 1997.

- Goeken JA, Kingery JD. Laboratory recognition of celiac disease/gluten-sensitive enteropathy. CAP Participant Summary, 2007 CES-A.

- Green PH, et al. Celiac Disease. N Engl J Med 357:1731-42, 2007.

- NIH Consensus Conference on Celiac Disease. Gastroenterol. 128, no. 4, Suppl 1, 2005.

- Prause C. et al. Antibodies Against Deamidated Gliadin as New and Accurate Biomarkers of Childhood Coeliac Disease. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutrition: 49:52-58, 2009.

- Prause, C et al. “Give us this day our daily breat”—evolving concepts in Celiac Sprue. Arch Pathol Lab Med 132:1594-9, 2008.

- Ludvigsson FJ et al. Small-intestinal histopathology and mortality risk in celiac disease. JAMA 302:1171-8, 2009.

- Celiac Sprue Association Website http://www.csaceliacs.org/celiac_symptoms.php

- National Digestive Disease Information Clearinghouse (A Service of NIH) http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/celiac/

- C. Robert Dahl, MD, "Celiac Disease: The Great Mimic Presentation," CSA Annual Conference, September 2000.

- Scoglio R, et al. Is intestinal biopsy always needed for diagnosis of celiac disease? Am J Gastroenterol 98:1325-31, 2003.

- Villalta D et al. IgG antibodies against deamidated gliadin peptides for diagnosis of celiac disease in patients with IgA deficiency. Clin Chem 56:464-8, 2010.